In 2007, Steve Jobs took center stage at MacWorld in San Francisco to announce and demo Apple’s new product – the iPhone smartphone. He wanted to give a live demo even though the phone prototype, still months away from completion, had many bugs and barely worked. This caused many nervous mishaps during his rehearsal presentations the week before, but Jobs knew he was about to make history [1].

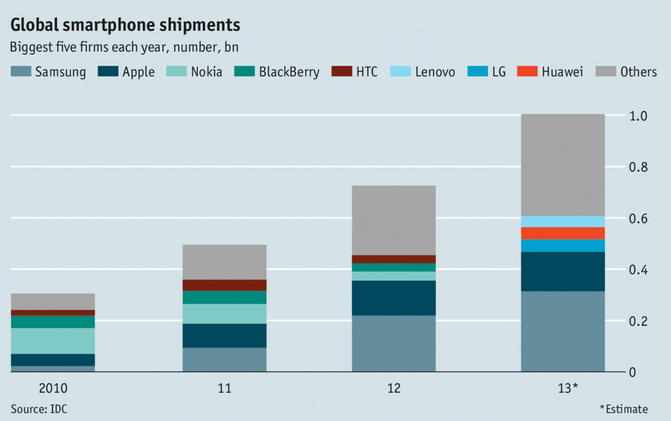

Three years after iPhone’s rollout, Google released its open source Operating System (“OS”), Android. By 2013, 30% of the global 5.2 billion mobile phone users had smartphones.

As of May 2014, a quarter of global web views are accessed via smartphones. Meanwhile, research shows the average person checks his phone 150 times per day. The story of smartphones’ rapid growth has just as much to do with people’s shifting views of these devices from a luxury good to a necessity as it does with competitive forces seeking to dominate. Each year, competitors challenge one another to create better, faster, and cheaper products. This subject of this essay is smartphones, but it’s really the story of how companies survive through an industry’s growth and maturation.

Apple and Android Background

| Apple | ||

| Phone Software | iOS | Android |

| Phone Hardware Company | Apple | Samsung, HTC, LG, etc. |

| Price per phone in 2013 (unsubsidized) | $650 | $276 |

| U.S. Smartphone Market Share, 2014 | 41.6% | 51.7% |

| Global Smartphone Market Share, 2014 | 18% | 78% (Includes forked versions Google does not control) |

| 2013 Growth Rate | 20% | 125% |

Because Apple and Google almost split market share for smartphones in the U.S., many American smartphone owners view them as direct competitors. However, they actually have very different strategies for user acquisition and revenue growth, and these differences will play out largely in the next phase of growth into the developing world.

The iPhone has one software and hardware developer – Apple. As the monopoly producer of iPhones, Apple enjoys complete control over how the iPhone looks, feels, and works. And more importantly, its price. Apple collects a very high 50-60% gross margin on each phone sold, one of the reasons Apple is the most profitable non-oil company in the world.

Google takes a different tactic by making the Android OS code free and partnering with third party manufacturers like Samsung and LG.The potential for scale was simple – Google created the software only and didn’t have to worry about managing manufacturing costs, procuring raw goods, or coordinating supply chains.

Software is expensive initially due to high R&D costs, but once a product is created, scaling that to millions of users is quite cheap.This enables Google to set sights on one day offering a device to every person. However, this diversified production strategy also creates significant fragmentation. For example, Animoco, an Android game developer, has to test its Android apps on over 400 devices.

The Exponential Growth Years (2006 – 2014)

There are three key factors that have driven the exponential smartphone growth up to today – intense marketing to new users, ecosystem lock-in for existing users, and manufacturing strategies designed for scalability.

Growth first starts with strong reinforcing feedback loops. In the beginning, Apple invested significantly in advertising and publicity campaigns for the launch of its first iPhone. As we see in the growth systems model below, advertising led to greater demand, which fueled more revenue for future advertising (“R1” or “Reinforcing Loop 1”). Also with more revenues, Apple could invest in retail stores to demo products directly to users (“R2”), further reinforcing revenues for future investment.

The reinforcing loops above, which required significant upfront spending from Apple, were necessary to launch Apple into the exponential success archetype, where growth fuels itself. Soon, customers and the media become Apple’s greatest marketers. In the systems model below, word of mouth advertising and media mentions cost Apple nothing, making them very effective Reinforcing Loops.

But media buzz comes and goes with the daily news cycle before another hot product becomes the cover story. Also, both these loops can quickly turn into Balancing Loops that drive demand down if the public believes the product did not meet expectations created in original Advertising campaigns [2].

Success created market opportunity. Apple wasn’t just increasing the demand for the iPhone, but the whole smartphone market. So we can revise the systems model to differentiate iPhone market share from Smartphone Demand (below). This created opportunities for competitors to join the smartphone market, introducing the first Balancing Loop, “Competition” to our model. Three years after the iPhone’s arrival, Android emerged as the first legitimate competitor to the iPhone, debuting on HTC and Motorola phones [3]. Android phones would quickly overtake the iPhone in absolute sales and market share.

Drivers of Growth: Pricing & Product Differentiation

A key reason for Android’s blazing growth is its pricing strategy. The unsubsidized iPhone costs over $650, while the average Android phone costs half that price, a gap that grows wider and wider every year [4]. This price premium has made the iPhone a device for high-end customers, and while there are equivalent Android high-end devices, cheaper Android phones quickly became the most viable option for the larger price-sensitive consumer market especially in developing markets [5].

However, Apple is only able to charge high prices insofar as it successfully differentiates its product as a superior device. Product differentiation strategies include adding features, improving functionality, or providing excellent customer support.

Drivers of Growth: Ecosystem Lock-in

After these companies acquire new users, they face the challenge of converting consumers into loyalists. Companies look to differentiate their smartphone experience by creating communities, interactions, and engagement unique to its ecosystem. Apple has this down pat.

The iPhone is well-integrated with other Apple products – when the iPhone first came out, it carried over the technology that people already loved about the iPod and synced iPhones with consumers’ entire iTunes libraries. Later, exclusive services like iMessage, FaceTime video chat, and iCloud photo backup have become user favorites that exist in multiple Apple devices and will never make their way to Android.

The result? Apple attracts a high number of Android defectors, while rarely losing users themselves. Apple loyalists starve for new Apple releases, forming long lines in front of Apple retail stores on each new launch date.

The Apple Ecosystems is composed of many apps, software services, and hardware. Source.

Android is different – Google’s business model wants its users’ data and its own services to be universally accessible on any platform. This has made Gmail, Google Maps, Google Search, and Youtube ubiquitous. This is Google’s ecosystem lock-in – it doesn’t matter whether you’re using a Mac, iPhone, Android phone, or any hardware product. You will still “google” things.

Meanwhile the multitude of Android phone manufacturers, by all signing on with Android, have little opportunity to create their own Samsung or Motorola specific ecosystems. But Google doesn’t care because more partnerships leads to more users within the Google ecosystem.

Another crucial Apple differentiation point is its deep and varied App Store. Many businesses debut their mobile apps on Apple’s App Store instead of Google Play (Android’s store). This is partly because many developers themselves prefer iPhones and also because Apple has strong monetization design like in-app purchases for developers to make money.

In absolute revenues, developers make significantly more from iOS apps, even though Apple’s App Store has fewer apps than Google Play.

Meanwhile, Apps are becoming increasingly important as mobile users spend a greater percentage of their mobile time share in Apps.

When Smartphone Growth Stagnates (2014 – )

With developed countries like the US and Europe having had smartphones for over half a decade, they will eventually approach an upward ceiling capped by the size of the population (Limits to Growth archetype). Most industry growth will come from developing areas like South America, Africa, and Asia. The speed with which this situation developed and the difficulty of growing share in an established market with entrenched incumbents have made it even more clear that the window of opportunity in the developing world will be short.

Prices of smartphones in these developing areas are falling even faster than many companies have anticipated. Increasing number of companies are forking the open source Android project to sell their handsets at cost. Software nonprofits like Mozilla and Tizen are creating their own software with drastically low price points to undercut the already-low $200 Android smartphones. Local phone companies like China’s Xiaomi and India’s Micromax Mobile that are better positioned to cater to specific cultural preferences have quickly begun to steal market share. Meanwhile, large conglomerates like LG and Lenovo are able to sell each phone at a loss in order to have a piece of the pie. Welcome to the competitive market of a maturing industry.

Despite all these new areas of growth, users in developed markets are still extremely valuable because they cost more to acquire (through advertising) and they yield more revenue through cross-selling other services. For example, newcomer Amazon is pursuing this strategy with their e-commerce driven Fire phone, where users can point their phones at anything they see or hear and see an option to purchase the item on Amazon.com. Google makes lots of revenues off advertising, and Apple makes plenty of profit from each app store purchase or iTunes sale.

Who Wins

This brutal competition in mature markets will ultimately create superior smartphones and benefit consumers tremendously by allowing them access to a fantastically productive technology faster than it could have ever happened in previous history. It took electricity 15 years and the telephone 39 years to reach 40% penetration in the US. Smartphones have done it in just four.

Mobile phones have already changed entire societies. Remote villages do not have electricity and water but can call each other from their mobiles. Before long, they will be able to use a cheap smartphone far more advanced than the “cutting edge technology” Steve Jobs introduced in 2007 to make calls, transfer money, or research information.

Essay Written by Jonathan Yu and Jenny Zhou

Footnotes

[1] And Then Steve Said, “Let There Be an iPhone”

[3] Wireless carrier Cingular (now called AT&T) had exclusive rights to distribute Apple’s iPhone for the first 4 years of existence. Competitor Verizon responded to this exclusivity with the “Droid” phone campaign.

[4] That is a partial goal of the Google Nexus program – sell otherwise high end hardware at low-margin or at-cost prices. The Nexus One first sold for $530 unlocked in 2009, cheaper than the standard high-end smartphone’s $649 price tag. Four years later, the high-end Nexus 5 debuted at $349, undercutting almost every other Android device on the market.

[5] In the United States, carrier service providers often subsidize part of a phone’s price to encourage cellphone subscribers to sign a two-year contract. An American iPhone owner never has to pay the full $600. However this business arrangement doesn’t exist in developing countries like China, India and Brazil. Apple does offer older models of the iPhone to customers at lower prices, but prices still make up a high percentage of a consumer’s disposable income.

The American service provider’s subsidy model is unlikely to happen in developing countries because it requires creditworthy customers that profit-seeking companies can trust with two-year contracts. However the model has worked well in wealthy countries like Japan. Service providers there like NTT Docomo, KDDI, and Softbank – looking to take market share from each other in the mature Japanese mobile operator space – provide aggressive subsidies for the iPhone. In 2013, three out of every four smartphones sold in Japan – the world’s fourth biggest smartphone market – was an iPhone. It is Apple’s fastest growing foreign country and most profitable as well with 50+% operating margins.

5 comments